The Globe & Mail reports:

Katya Orlova’s favourite drinks were the canned gin-and-tonics sold by vendors on nearly every street in Moscow. She downed as many as 10 a day. Dasha Vodneva mixed her cocktails with vodka. Years of heavy drinking landed both in a Moscow rehab centre.

Katya is 13; Dasha just 12. They’re patients at Kvartal, Russia’s only treatment centre for teenage addicts. The girls don’t miss drinking now, but both are leaving soon and neither has a plan for staying sober.

“I want to stop drinking,” said Dasha, whose solemn face is framed by long, wavy brown hair. “Here, they explained to me [that] drinking is harmful to my health. Maybe I will stop. I’m not sure.”

Katya shrugged when asked why she drank. “I don’t know – because I wanted to forget my problems with my mom.” Then, as if the questions were boring her, the raven-haired tomboy resumed doing handstands against a wall.

Another patient, Sabina Pasechnik, 15, said she’ll likely resume drinking when she leaves Kvartal. The pressure in some Moscow teenage circles is too great. “It’s considered normal behaviour,” said Sabina, whose own mother is an alcohol counsellor.

“I don’t know how it will be possible to live without it. But at the same time, I want to stop.”

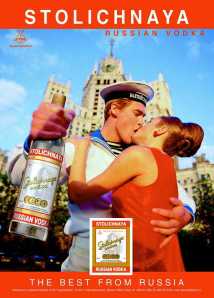

Russia has always been a hard-drinking nation. Its history and literature are rife with folklore that tends to romanticize the Russian fondness for vodka. In recent years, those habits have been passed on to a younger generation of drinkers.

Alcohol addiction among teenagers and children has soared since the collapse of the Soviet Union. According to Russian Ministry of Health statistics, the number of children under 18 who are addicted to alcohol has risen from about 6,300 in the early 1990s to nearly 20,000 in 2007. Each year, the numbers creep higher.

Moscow parks, subway stations and plazas are common watering holes for young Muscovites. At Kaluzhskaya plaza in central Moscow, hundreds of youths and teens gather around a large Lenin statue every Thursday night, even during the coldest winter evenings, and drink until early morning.

Experts say rampant poverty and the social upheaval in the 1990s helped spur the spike in alcoholism rates among the young.

“They’re from impoverished families or they have dropped out of school or their parents are hard drinkers, too,” said Veronika Gotlib, the director of Kvartal, which opened five years ago. It treats about 300 patients a year, just a fraction of the thousands of addicted teens. Most are between the ages of 12 and 16, but patients have been as young as 7.

Although Russia’s legal drinking age is 18, children say it’s easy to buy alcohol from street vendors. Twelve-year-old Dasha persuaded older friends to buy her cocktails; others made the purchases themselves.

Ms. Gotlib said many of the children are brought to the centre by exasperated parents; others after run-ins with police.

“Some of the stories are like from a Stephen King novel, just heartbreaking horror stories,” Ms. Gotlib said. But there are plenty of kids from average families too.

Kvartal is funded mainly by the Moscow city government but also gets money for programs from international aid agencies such as Unicef and the Canadian International Development Agency. Like many Western addiction treatment centres, it uses group and individual therapy combined with classes in art and drama.

Most of the children thrive at Kvartal, Ms. Gotlib said. But the same problems re-emerge once they leave. More than half go back to their old ways, she said. This is where Russia’s weak social-service system lags behind those of other countries.

Staff try to keep in touch with families of former patients, but many children are returning home to drinking environments.

“There isn’t enough support,” she said. We try to work with families and parents. But some of the parents don’t feel responsible. They ask us to fix their kids.”

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that child addiction rates are rising in Russia. The statistics mirror adult consumption rates, which have also soared since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Today, the average annual consumption for an adult is slightly more than 15 litres a year, almost double the rate from a decade ago and far higher than European and North American consumption rates.

Children from heavy-drinking families have few resources to dissuade them from following their parents’ paths.

“In my opinion, they have a lot of free time and they are not engaged in any activities,” Ms. Gotlib said. “If you don’t find love at home, you go into the street. And there in the street they meet other kids and they begin drinking in groups.”

Dasha started drinking at 10, she said, mainly to escape the crowded two-bedroom apartment where she lived with her father, stepmother and four other relatives. She left her mother’s home in Omsk in Siberia because her stepfather beat her. But in Moscow, her father was just as abusive. At first, the sugary cocktails made her nauseous and dizzy, but she liked the warmth it brought her. School authorities sent her to Kvartal last fall after she was found smoking in the bathroom.

Dasha has been living at Kvartal ever since. She likes the calm atmosphere, the structure and even the counselling. “It’s a good break from my house.”

But the girls interviewed were leery about what’s in store for them once they leave.

Dasha Beskova, 14, said she wants to drink in moderation, just on holidays and at birthday parties. Sabina said she doesn’t know how to live without drinking.

“That was part of life, to drink. Now, if I go to a restaurant, of course I would want to drink. I liked being drunk.”

Thirsty nations

Annual alcohol consumption, litres per person:

15 Russia

11.2 Britain

9.8 Australia

8.4 United States

7.6 Japan

1.5 Turkey